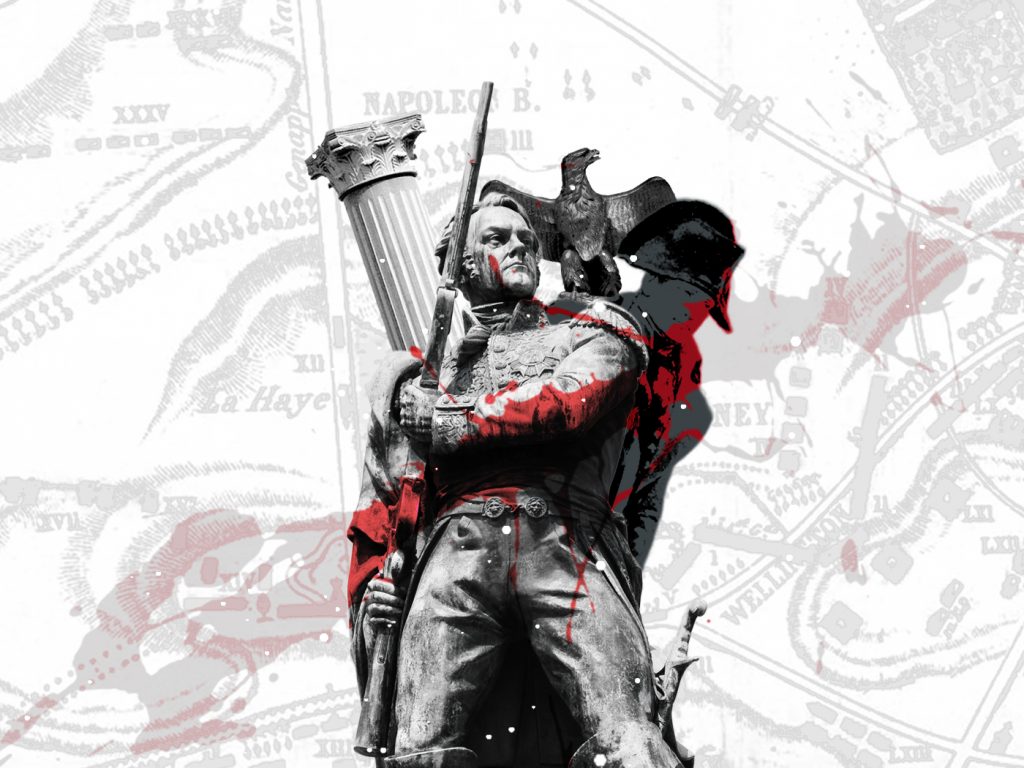

Michel Ney rose from humble beginnings to become one of Napoleon’s most legendary Marshals. His tumultuous life is a saga of unlikely rise, boundless courage, and awe-inspiring feats, yet also one of relentless violence and ultimate tragedy, a mirror to the ruthless age he inhabited.

Prologue

In July 1789, when hundreds of Parisians stormed the imposing Bastille fortress, they could hardly have imagined that their country’s foundations would soon be radically dismantled and restructured in much the same way as those of the notorious state prison. The nascent French Revolution was a seismic event forever altering the sociopolitical contours of France and rippling across Europe, if not most of the planet.

The Revolution abolished feudalism, declared universal rights, and embraced secular republicanism. It also introduced meritocracy—meaning societal advancement was based on talent and achievement rather than birth or wealth. The ancient hierarchies that for ages had bound Frenchmen to their birthright and the depths of their pockets were decisively shattered.

No one embodied France’s meritocratic turn better than a nobody from the distant, rural, independence-thirsting Mediterranean island of Corsica. After a decade of revolutionary turmoil, young general Napoleon Bonaparte—driven by an unshakable self-belief, coupled with immense aura, political instinct, extraordinary fortune, and pure genius—took the reins over republican France and even dared to make it an empire five years later.

For one and a half decades, the offspring of a poor family from the Corsican lower nobility improbably not only ruled France but bent all continental Europe to his will.

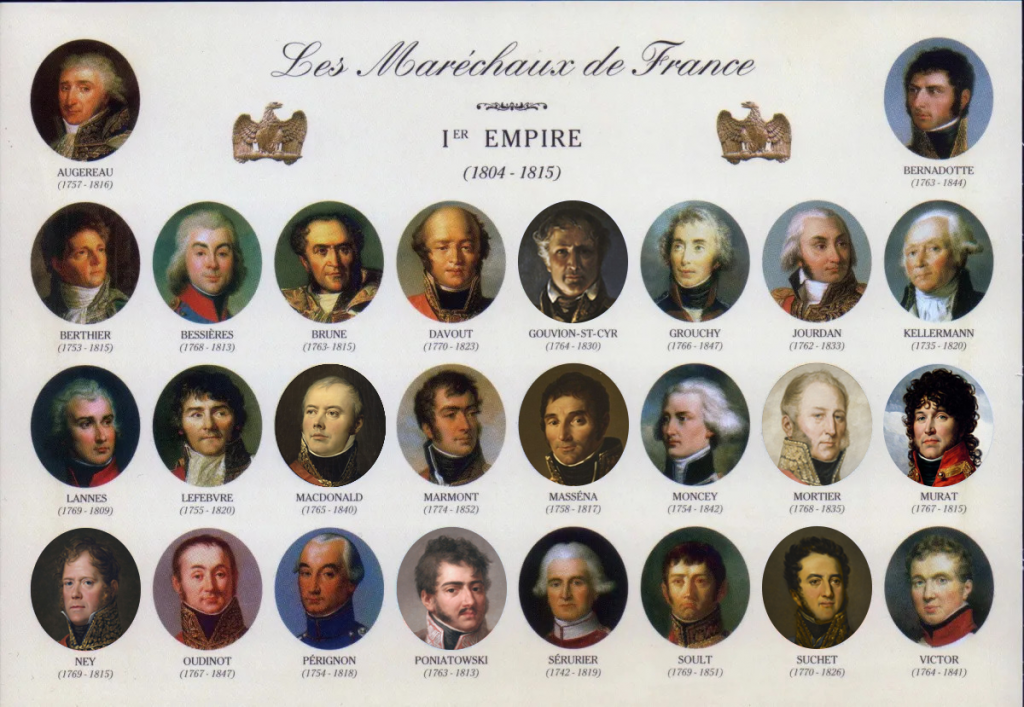

Alongside his self-coronation as Emperor in 1804, Bonaparte introduced the title of Maréchal d’Empire, establishing a new merit-based aristocracy founded not on noble ancestry but on talent and personal achievement. Though the title of Marshal was formally a civil honour—granting its holders immense wealth, power, and respect—it was, above all, a mark of foremost military distinction.

Napoleon’s 26 Marshals were larger-than-life characters, forming one of history’s most extraordinary collection of commanders. Without them, Bonaparte would not have ascended to the transcendent figure he is. For his Marshals, nearly as much as their master, were dreaded dealers in thunder and death—even, at times, to their own men.

Though not expected to lead from the front, they often braved the thick of battle, personally courting death on the increasingly blood-soaked fields of Europe. In Napoleon’s pursuit to expand French hegemony—veiled beneath the Trojan horse of spreading enlightenment—his premier generals waged war from Porto and Madrid to Rome, Venice, Vienna, and Berlin, all the way to Cairo, Warsaw, and Moscow. It would take a continent in arms and millions of deaths to force them back into the French hexagon.

Notorious for their petty jealousies over the Emperor’s favour, Napoleon’s Marshals “were to be called callous, greedy, treacherous, rapacious, brutal, and a hundred other things.” Yet, as 20th-century British writer R. F. Delderfield eloquently put it: “There is only one word that no writer has ever dared to use in respect of any one of them. That word is ‘coward.’”[1]

One of Napoleon’s most famous Marshals was Michel Ney. Celebrated by Hugo and Hemingway and regretted for the dire futility of his actions by Tolstoy, Ney is a legendary figure, whose memory reverberates to this day. Not without reason, Napoleon himself, never one to lavish praise lightly, called him “the bravest of the brave.”

The following text is both a homage and a panopticon of Ney’s moving and ultimately tragic life. It is a tale of an unexpected ascent and boundless courage but also one of immeasurable violence and trauma.

Humble beginnings

Born in 1769 in Saarlouis—a French exclave in the Saarland region now part of Germany—and thus bilingual, Ney’s life seemed destined for ordinariness. At 18, two years before the Revolution, the son of a humble barrel-maker abandoned his brief civilian career and enlisted as a hussar (a light cavalryman) in the army of the Ancien Régime.

As the Revolution unfolded and France clashed with its monarchical neighbours, the skilled horseman and sabrefighter understood that birth, lineage, and influence were no longer the determinators for advancement and devoted himself to the army, one of France’s emerging centres of power.

It was during this time that the talented Monsieur Ney fought his only recorded duel, which was a grave offense at the time. Such was Ney’s reputation as a fencer that, when his regiment’s fencing instructor was defeated in a duel by his pendant of a rival regiment, his comrades chose him to restore their honour.

In a sharp encounter, the future Marshal struck a devastating blow to his opponent’s wrist, ending the man’s career as a fencing teacher forever. Years later, as a wealthy and esteemed general, Ney sought out his former adversary and found him living in poverty. Honourable as he was, Ney arranged a pension from his own purse, ensuring the man spent his remaining years in comfort and dignity.

France’s unlikely victory against the First Coalition in the 1790s then propelled Ney’s rapid rise through the ranks. In less than seven years, sometimes witnessing successive promotions within weeks, Ney ascended from unknown hussar ranker to Division General by 1799, the highest French military rank available by then. Mainly fighting in the German theatres of war, Ney had earned his ascend at a cost—five wounds, at least one severe, and a month as prisoner of the Austrian arch enemies.

It was not the first promotion Ney, only 30 years old and citing a lack of experience, had attempted to refuse. However, the upheavals of the Revolution and the following Reign of Terror had dramatically depleted the French officer corps, while the wars against the despised kings of Europe cried out for qualified leadership. During this era, the meteoric rise of soldiers from humble origins—unthinkable only a few years prior and still impossible among France’s enemies—became far from rare.

Standing at 1.73 meters (taller than the average for his time) with a robust build, a short torso, long legs, and distinctive curly sideburns, Ney cut an imposing figure. His fiery red hair mirrored his hot-blooded temper. Yet, beneath this volcanic exterior lay a generous and sentimental heart, as he was “quick to take offence but just as quick to forgive everything but an insult touching his honour.”[2]

Michel Ney thus embodied the quintessential post-revolutionary French soldier: fearless, bold, decisive, always at the forefront of battle, and always last to retreat. Ney was one of only three generals from the Army of the Sambre and Meuse whom Napoleon, having earned his laurels in Italy, elevated to a Marshal of his revolutionary Empire in 1804.

“That man is a lion”

Known among the soldiery as L’Infatigable (the tireless), Ney, who was only 35 years old when made Marshal, was not to serve directly under Napoleon until 1805. When the Third Coalition threatened the upstart Empire, Ney’s VI Corps of the Grande Armée—toughened by two years of preparing an invasion of old-nemesis Britain that never came to pass—was summoned to fight in southern Germany.

Under the Emperor’s watchful eye, the now Marshal commanded his corps with unrelenting vigour. Ney’s victories, most notably at Elchingen, Bavaria, played a crucial role in closing the trap around the unfortunate Austrians, leading to their humiliating and bloodless surrender. The campaign later earned Ney the title Duke of Elchingen.

The following year, amid Napoleon’s crushing campaign against the hapless Prussians, Ney’s less admirable qualities came to the fore—among them headstrong impulsiveness, tactical overconfidence, and an inclination for reckless daring.

At Jena in 1806, while spearheading the cavalry of his corps, the barrel-maker’s son launched an unauthorized attack on the Prussian centre. A decision that almost led to catastrophe. While succeeding initially, the red-haired Marshal and his troops soon found themselves overextended and under heavy artillery fire.

Sensing an opportunity, the Prussian generals swiftly ordered a counterattack, enveloping Ney’s vanguard and isolating it from the main French force. Surrounded and with no route of retreat, Ney’s troops were forced into a defensive square, bracing themselves against attacks from all sides.

Napoleon, little pleased but ever the master of adaptation, quickly grasped the imminent danger facing his impetuous commander. The Emperor directed Marshal Lannes and his men to break through and rescue Le Rougeaud (the red-faced) from his precarious position—saving Ney and his battered forces from what might otherwise have been their ruin.

Ney was to win back the Emperor’s favour with the decisive battle of Friedland against the Russians in 1807, in which VI Corps executed the key manoeuvre and secured victory. As Ney’s troops surged forward at the head of the right wing, their advance unrelenting despite heavy artillery fire and a desperate charge by the Russian Imperial Guard, Napoleon, observing the scene with admiration, remarked, “That man is a lion.”

Ney in Iberia: “This proud fellow will upset all our plans”

After Friedland and the Peace of Tilsit, Napoleon was at the peak of his power, dominating the European landmass as the continent’s most powerful man in centuries. However, things slowly began to unravel as his Empire faltered under its own weight.

After almost a year of tranquillity, war was on the horizon again, this time in Iberia. Few French soldiers could have predicted the six-year quicksand awaiting them. Hundreds of thousands of them would find death in the treacherous villages and on the barren plateaus of the peninsula.

The unforgiving struggle against the Spanish, the Portuguese, their British allies, and tenacious local guerrillas revealed not only some of Ney’s finest talents but also some of his gravest flaws. Though Ney was mostly a generous foe and true to his egalitarian vein, unpretentious and approachable with his men, he could also be a nightmare of a colleague. During the Peninsular War, his fellow Marshals Soult and Masséna had to learn this the hard way.

When, in 1809, Marshal Soult’s II Corps, recently driven out of Porto by the British, stumbled into northwest Spain in a sorry state, Le Lion Rouge was in no mood for cooperation. At a tense meeting, Soult—a rival of Ney since their days in the Army of Sambre and Meuse—demanded support to replenish his depleted army. Ney, however, was reluctant and taunted his Marshal colleague so fiercely that the situation nearly escalated to a duel, which the staff officers present had to avert with great difficulty.

A year later, the French launched another attempt to invade Portugal and expel the British under the Duke of Wellington. Napoleon entrusted the 52-year-old Marshal Masséna to get the job done. Second only to Napoleon in military reputation, Masséna, however, was feeling the wear and tear of time and showed little enthusiasm for the daunting task. The hot-headed Ney, 41 at the time, believed himself the better choice and, from day one, worked hard to obstruct the methodical Masséna.

Ney wasted no time in getting under the skin of his fellow Marshal and nominal superior. When Masséna send an experienced engineer officer to assist Ney in besieging a fortress at the Spanish-Portuguese border, Le Rougeaud responded with an audacious letter that openly defied the order.

“I am a Duke and a Marshal of the Empire like you; as for your title of Prince of Essling, it is of no importance outside the Tuileries,” he wrote. Adding insult to injury, Ney continued: “They say your man dances prettily: all the better for him; but this does not prove that he can make those mad Spaniards dance, and that is what we want.”

Infuriated, the usually laid-back Masséna threatened to relieve Ney of his command, forcing the latter to begrudgingly comply. Yet, Masséna’s anticipation should prove somewhat prophetic: “This proud fellow will upset all our plans with his stubborn self-will and foolish vanity.”

But Ney had brought more than just his explosive temper and uncollegiality to the peninsula. Alongside his blue Marshal’s baton, he also carried his recklessness in battle. This became evident when, after his VI Corps had forced a British division across the Côa River, the defeated Redcoats regrouped on the far bank. The British took up positions on the heights above a narrow stone bridge, which was the only viable crossing, and entrenched themselves.

Ney answered with his go-to-move: the unrelenting frontal assault. In three successive attacks through the bottleneck, his infantry, under an inferno of British-Portuguese fire, unsuccessfully attempted to force their way across the bridge. Ney’s columns pushed on until the bridge “was absolutely blocked by the bodies of the killed and the wounded, and till they themselves had been almost literally exterminated.”[3] With his senseless assault, Ney had snatched defeat from the jaws of victory.

When the French army under Masséna and Ney, now united, finally advanced on Lisbon, their first major engagement was an even bigger disaster, thanks not least to our protagonist. Again, the British had taken a defensive position, this time along the wooded Busaco ridge, concealing their true strength behind it. Although a route to outflank them existed, Masséna made no move to pursue it, assuming the French were only facing a rearguard.

Spurred on by Ney’s insistence, the French instead opted for a fierce frontal assault up the rocky and densely forested hills that were full of elite British sharpshooters. Perhaps sensing impending doom, Ney uncharacteristically oversaw the Sisyphean upward attack from the foot of the hill.

By dusk, the beaten French had suffered around five thousand casualties (killed, wounded, or captured). Despite having advocated for the attack, Ney now vocally condemned it, shamelessly blaming Masséna for ordering a frontal assault on such a strong position.

“A perfect lesson in the art of war”

Up to this point of the fruitless Portuguese campaign, Ney had been a testy troublemaker, openly defiant and at times outright malicious. Yet, when Masséna was finally forced to call the invasion quits, Ney—tasked with commanding the rearguard back into Spain—revealed his finer qualities: masterful tactics paired with tireless vigour. It was to serve as a prelude to his fabled odyssey out of Russia just over a year and a half later.

Day after day, Ney’s troops contested the British pursuit through energy and deception, handing Wellington one bloody nose after another. If the British vanguard advanced too quickly, the French would suddenly turn and strike. If the pursuers fell behind, the French secured a day’s march to the pivotal river crossings on the Portuguese-Spanish border. Ney’s skilful retreat earned him admiration even from his adversaries. One British general involved remarked that his rearguard was a “perfect lesson in the art of war.”

The relationship between the Marshals Masséna and Ney, however, was anything but perfect; rather, it was beyond repair. When Ney refused to follow new offensive orders without written confirmation from Napoleon, Masséna finally dismissed the quarrelsome Marshal from command of VI Corps and sent him back to France. Ney’s soldiers assembled on parade to bid farewell to the man who, following Marshal Lannes‘ death in Austria, had become the most beloved figure in the Grand Armée.

Apparently, Napoleon was not overly bothered by Ney’s indiscipline. In fact, the Emperor himself frequently stoked the flames of jealousy among his Marshals. After a few rare months of peace with his wife and children at their countryside chateau, Ney was given a new command, while the unfortunate Masséna was sent into retirement two months after the incident.

In the realm of forest and snow

As Napoleon and his unfaithful ally, the Russian Tsar, stumbled towards confrontation—a high-stakes game of chicken with no side willing to back down—Ney sought to restore his tarnished reputation. The fateful invasion of Russia that began in June 1812 was to earn him his place in the pantheon of Napoleonic legend.

The Emperor, mindful of Ney’s gift for leading men, assigned him III Corps in the reorganized Grande Armée. Like much of the army, III Corps was a mosaic of nations and tongues, Württemberger, Portuguese, Croatians, and Dutch among them, with less than a third of its ranks French.

On the arduous march to Moscow, Ney distinguished himself in the carnages of Smolensk (where he was wounded in the neck) and Borodino, the bloodiest single day in Napoleonic history, where he led a daring charge against the heavily fortified Russian centre. Ney’s true trial of strength, however, would unfold in October, when Napoleon was forced to evacuate the eerie, burnt-out Moscow.

The Grande Armée, reduced to one-fifth of its original strength, had morphed into a caricature of itself. Loaded with plunder and wrapped in looted, precious furs, the soldiers trotted westwards through a frosty, desolate landscape. With discipline and camaraderie rapidly deteriorating, the march turned into a grim struggle for survival.

To make matters worse, the column, stretching up to 100 kilometres at times, was pursued by Cossacks (mobile, irregular horsemen from the southern steppes of the Russian Empire), who gathered like flocks of vultures to hang upon the army’s side and rear.

When heavy snowfall set in, Napoleon assigned Ney’s corps with the unpopular task of guarding the rear. Ney, however, took on the mission without batting an eyelid. Amid icy storms and occasional Russian artillery fire, he led by example, urging on his starving men, sometimes as one of the rearmost men under the flag.

“It is impossible to show greater bravery!”

Soon after reaching the relative safety of Orsha, Napoleon grew increasingly anxious about Ney, who seemed to have been lost. The Emperor knew that the troops of Miloradovich, one of Russia’s bolder generals, had outpaced parts of the retreat and set up a roadblock, cutting off Ney’s corps from the main force. Napoleon stated that he would give every one of the three hundred million francs in the Tuileries to get his Marshal back.

Ney now barely had 6,000 infantrymen, a lone squadron of cavalry, and 12 cannons under his command—less than one seventh of III Corps’ original strength. Meanwhile, Miloradovich and his 20,000 men, having already let Prince Eugène and Marshal Davout slip through their fingers, were eager not to squander a third chance to conquer one of Napoleon’s legendary commanders.

On 18 November 1812, Miloradovich sent an officer to demand Ney’s surrender. The Russians, numbering approximately 80,000 in the area, went so far as to invite French officers to verify their numbers firsthand if they had any doubts.

When Russian artillery fire broke out, presumably triggered accidentally, Ney’s response to the Russian emissary was one of typical stubbornness: “A Marshal of France does not surrender. One does not negotiate under the fire of the enemy. You are my prisoner.”

Ney then lined up his forces, unleashed his six guns, and led an energetic frontal assault against the massive Russian roadblock. Through thick fog and snow, the attackers nearly overran the enemy artillery but were repelled by devastating canister fire and a Russian countercharge, causing terrible losses.

Impressed, Miloradovich told a captured French officer, “Bravo, bravo, Messieurs les Français. You have just attacked, with astonishing vigour, an entire corps with a handful of men. It is impossible to show greater bravery!”

“Everything is fucked!”

When it dawned on him that Napoleon had left him to fend for himself, Ney was infuriated: “That bastard has abandoned us; he sacrificed us to save himself; what can we do? What will become of us? Everything is fucked!”

Refusing to consider surrender as an option, Ney rallied his battered forces and, to everyone’s surprise, began leading them back eastward toward Smolensk. When some of his men hesitated and questioned the order, Ney declared, “Very well, I’ll go back to Smolensk alone!” Still, surrender appeared to be only a matter of hours away.

However, as one of the surviving officers recalled:

The presence of Marshal Ney was enough to reassure us. Without knowing what he intended or what he could do, we knew that he would do something. His confidence in himself was equal to his courage. The greater the danger, the more prompt was his resolution, and once he had decided what course to take, he never doubted of success.

As daylight broke the next morning, the Russians prepared to accept the surrender of one of Europe’s most famous soldiers. But to their astonishment, Ney and his men had disappeared, leaving behind only campfires. Assuming they had turned east, the Russians decided to continue pursuing Napoleon’s main force, leaving it to the Cossacks to finish Ney’s doomed rearguard.

The night before, Ney had made up the daring plan to evade the Russians by crossing the Dnieper, which flowed to the north, parallel to the Smolensk Road. Once across, he planned to head west toward Orsha, aiming to reunite with the main body and thus placing the river between himself and the Russians.

Ney had halted at an abandoned village, lighting extra fires to feign a larger presence. At 8 p.m., he left a few men to tend the fires and quietly led his column off the Smolensk Road into the woods to the north. The march was gruelling, as guns and supply wagons had to be dragged through deep snow. After quickly losing orientation, Ney located the Dnieper by breaking the ice of a stream and discovering which direction of the current to follow.

By 9 p.m., the men reached the riverbank. The ice had partially thawed, but with a strong frost setting in, Ney chose to delay the crossing until after midnight. The extra time would firm up the ice and allow more stragglers to catch up. After giving his orders, the Marshal had the nerve to wrap himself in his coat, lie down in the snow, and sleep soundly until it was time to cross.

When the soldiers began crossing, they maintained distance between each other as they tested the ice with their musket butts. With every step, the ice creaked threateningly. The only safe method was to send the men across in single file at several crossing points, guided by lighted fires on both banks.

After most of the infantry and many stragglers had crossed, an attempt was made to send horses and wagons over the ice. A few crossed safely, but in doing so, they weakened the frozen surface. As more wagons ventured out, the ice gave way with sickening cracks, plunging the unlucky into the frigid waters below. A wagon carrying wounded men broke through and untraceably vanished into the darkness. Everywhere, men struggled in the icy water or desperately clung to the ice, pleading with their comrades for rescue.

Once again, Ney led by example, personally joining the rescue efforts. Crawling on all fours across the ice, he reached the gaping hole and pulled to safety a man who was clinging to the shattered edge. Following the accident, it was determined that all the guns, wagons, and 300 wounded men would have to be abandoned to their fate on the south bank.

“You are one more victim of the war”

Ney’s hope that the far side of the river would be free of enemies proved deceptive. There, too, marauding Cossacks were up to no good, picking up the trail of the column and killing everyone outside the safety of the marching ranks. Ney’s men had to trudge through knee-deep snow, relentlessly stalked by their pursuers who continued to thin out their already heavily decimated ranks.

“Those who get through this will show they have their balls hung by steel wire!” Ney, on foot among his men and the very heart and soul of the desperate resistance, roared, spurring them on with vulgar tirades about the looks and cowardice of the Cossacks. When they approached, the Marshal would sometimes personally load his musket, take aim and shoot one of the wild lancers from his saddle.

But the horrors of the retreat inevitably numbed Ney and made him indifferent to the daily experience of death and suffering. When an officer spoke to him about the death of a close comrade, Ney remarked: “Well, it is better that we mourn him than that he mourns us.” And when a soldier collapsed wounded beside him, pleading to be carried away and saved from the advancing Cossacks: “What do you want me to do? You are one more victim of the war.”

Three gruelling days after their failed attempt to break through the Russian roadblock, the lost rearguard finally came within sight of Orsha, from where Prince Eugène’s Italians fought through the night to rescue the fewer than 1,000 survivors. When Ney and Eugène met, they fell into each other’s arms in a tearful reunion that few had dared to hope for.

Upon hearing the news, the army’s main body erupted with joy, their spirits lifted by this much-needed morale boost for the final stage of the retreat. It was in this jubilant moment that an overjoyed Napoleon—who had not heard any good news for more than a month—dubbed Ney “Le Brave des Braves.”

A few days later, Ney was to play a pivotal role again during the dramatic climax of the retreat, the tragic crossing of the Berezina. By then, III Corps was in no condition to take on a combat role. When most generals and Marshal Oudinot went down during battle, Napoleon turned to Ney to stabilize the defence, which he achieved through several courageous counterattacks.

After all capable were across the Berezina, Ney once more took command of the rear. Arriving in Kovno (modern-day Kaunas), he organized defences to allow stragglers to pass, gather supplies, and escape across the Niemen into allied Prussia. With a few cannons and just a handful of disciplined men left, Ney held off the pursuing Russians.

His troops dwindled steadily—some killed or injured, others scattering. A company of Germans from Anhalt and Lippe threw down their weapons and fled after their Captain, wounded and despairing, put a pistol to his head and shot himself.

Ney grabbed their abandoned muskets and emptied them one by one at the advancing Cossacks. He “was, at that moment, just as one imagines the heroes of antiquity,” a survivor remembered. As he retreated across the bridge into Prussia, the Marshal fired a final shot at the astonished enemy before throwing his musket into the frozen Niemen. The Grande Armée’s last man under arms to leave Russia was Michel Ney.

On 15 December 1812, a worn-out, cloudy-eyed desperado stumbled into a military quarter in East Prussia. The man, dressed in a brown coat over a filthy uniform, was unrecognizable, his bearded face blackened by smoke. When the attending officer was confused, the maverick exclaimed:

Don’t you recognize me? I’m Michel Ney. I’m the rearguard of the Grande Armée! I have made my way here across a hundred fields of snow. Also, I’m damn hungry. Get someone to bring me a bowl of soup!

Ney’s stoic courage and resourceful initiative had not only preserved Napoleon’s honour and kept him from being captured or killed but also saved the lives of thousands of ordinary soldiers. Remarkably, Ney had emerged from the merciless fighting of the retreat without so much as a scratch, and though he appeared run-down in Prussia, his body was in perfect health. The same, however, could not be said for his mind.

“The army will not march!”

For his heroics in Russia, Napoleon bestowed upon Ney the title Prince of the Moskowa, elevating him to the Marshalate’s top-tier and showing the barrel-maker’s son off in Paris. Being the man of the hour meant little to the unpretentious Ney, who could not believe that, in 1813, with his army in ruins, Napoleon was reckless enough to resume hostilities against the reunited monarchs of Europe. The Emperor’s falling star and his many fatal miscalculations in Russia had already earned him Ney’s contempt.

The unimaginable agonies of the war in Russia had taken a toll on Ney. His usual temperament had changed into aimless anger and ever worse unpredictability, coupled with a melancholic readiness for death. Ney’s uneasy foreshadowing of the 1813 campaign in Germany was to be validated as early as the first battle, when fellow Marshal Bessières got his chest shattered by a cannon ball, killing him instantly. “This is our destiny; it’s a beautiful death,” Ney remarked when seeing his colleague’s corpse.

Ney’s energetic leadership in the newly raised French army, composed largely of raw teenage conscripts, was as inspiring as ever. However, his customary antics, paired with the mental fallout from his experiences in Russia, made him almost useless as an independent commander. One of the Marshal’s staff officers at the time described him as “feeble and indecisive, permitting himself to be led by others.” He further depicted Ney as reserved, uncommunicative, jealous of other Marshals, and harbouring a deep resentment toward Napoleon.

Ney’s weaknesses as a commander became evident during Napoleon’s push toward Berlin. At the Battle of Bautzen, the Emperor had planned to envelop the Prussian and Russian forces. Ney’s 84,000 troops were intended to deliver the fatal blow to the allied flank. However, misunderstanding one of Napoleon’s hastily scribbled instructions, Le Lion Rouge halted his movement when, by pushing on, he would have cut the outnumbered enemy off. Ney’s uncharacteristic hesitance robbed Napoleon of the chance to destroy the high-ranking allied army. One of the few chances to turn the tide of war was lost.

At the Battle of Dennewitz, not far from Berlin, Ney made another serious blunder as an independent general. His lack of forward reconnaissance and strategic foresight enabled the Coalition forces to reverse the battle’s momentum and inflict a devastating rout on his French army of 60,000. Ney was so upset that he contemplated suicide, writing to Napoleon: “The spirit of generals and officers is shattered, and our foreign allies will desert at the first opportunity.”

At the Battle of Nations at Leipzig, Ney, receiving a severe shoulder contusion, fought courageously under Napoleon’s guidance but could do little to alter the overall dire situation the French found themselves in. “Le Brave des Braves” recovered in time to join Napoleon as commander of the Young Guard in the 1814 campaign to defend the French home soil, in which the Emperor again and again outfoxed numerically superior enemies.

When the remaining Marshals realized they could no longer hold off the allies with their few exhausted and demoralized men, it was Ney who spoke for the Marshalate, demanding Napoleon’s abdication. “The army will not march!” he flatly said. And when Napoleon argued that the soldiers would obey their Emperor, Ney interrupted: “They will not, they will obey their generals.”

Ney’s opportunistic changeability was nothing new, though, for Napoleon, who unknowingly predicted the future by saying: “He was against me yesterday; he would get killed for me tomorrow.”

Insult and injustice

When Napoleon was sent into his first exile as Emperor of the tiny Mediterranean island Elba, the returning Bourbons did not hesitate to employ the war hero Ney. Yet, as France longed for peace, licking its wounds after two decades of war, the Bourbons and their aristocracy-in-tow lost no time in incurring the wrath of the people who had initially welcomed them back.

The Bourbon’s perspective was still thoroughly feudal, sustained by wounded pride and marked by deep disdain for their subjugates. France’s restored rulers behaved as if the Revolution had never happened. They sought to reimpose the chains of feudalism and blind obedience upon a people whom Napoleon had united behind revolutionary ideals, imperial glory and boundless individual opportunity.

The Bourbon aristocrats also set to establish an officer class among their own, with émigré officers looking for unearned rewards like the Légion d’Honneur, which under Napoleon had to be won on the battlefield and was now up for sale.

Bringing back their snobby etiquette, the aristocratic court society had no desire to welcome Napoleon’s dignitaries into their ranks. When his wife’s ancestry was insulted by a Royalist duchess, the spirited Ney—who had no disposition for court life and was still in his riding boots—stormed into the Tuileries, roaring: “I and others were fighting for France while you sat sipping tea in English gardens. You don’t seem to know what the name Ney means, but one of these days, I’ll show you.”

The new state of affairs and the barely concealed disrespect of their Royalist overlords weighed heavily on Ney and the other Marshals, who owed nothing whatsoever to birth and background. Ney, who now erratically alternated between rants against Napoleon and the Bourbons, had at heart not the welfare of any ruler but rather that of France.

Thus, Napoleon’s dramatic return from Elba, with its looming threat of civil war, struck him as profoundly troubling news. Scarred by the horrors of war, Ney felt obliged to protect his fellow Frenchmen from its recurrence.

“Can I stop the movement of the sea with my hands?”

Despite all the insults and injustices of the Bourbons, Ney famously promised King Louis XVIII to bring the escaped Napoleon to Paris in an iron cage. While he was dreading the prospect of a civil war, Ney was eager to butt heads with his old superior.

Now that there was a fight to be fought again, Ney found himself in a strange state of joyful excitement, mocking Napoleon’s march on Paris as a “crazy enterprise.” Ney anticipated that “that madman will never forgive me his abdication. He would be quite capable of cutting my head off.”

However, Ney soon found himself in a precarious position. As Napoleon advanced toward the capital, soldiers flocked his ranks, eagerly exchanging the royal standard for the Tricolore. Resisting the force of nature, Napoleon would mean provoking a futile civil war and thus needless bloodshed. Furthermore, Ney was deeply moved upon reading Napoleon’s proclamation to the army, melancholically remarking, “Nobody can write like that nowadays; this is the way to move soldiers‘ hearts!”

After all, it was not a Bourbon who had elevated him to the heights of Marshal, Duke, and Prince, but the charismatic Corsican. On the other hand, Ney’s soldierly duty bound him to the King, whose aristocratic supporters had never hidden their contempt for men of his breed.

At the end of the day, Ney was a blade with little to no political instinct, and it showed. While some of his fellow Marshals simply chose to retire and observe the unfolding drama from the sidelines, thus elegantly avoiding the crossfire, the Prince of the Moskowa was too emotional a character. Under the immense pressure of the crisis, his nerves cracked.

Understanding that the tide was firmly on Napoleon’s side, he complained: “Can I stop the movement of the sea with my hands?” One week after leaving Paris to confront the abdicated Emperor, Ney gave in to Bonaparte’s personal overtures. The Marshal assembled his troops and, to a jubilant crowd, declared that France had accepted Napoleon back, concluding with the shout “Vive I’Empereur!” Ney would later recall: “I was in the midst of the storm, and I lost my head.”

A few days later, Napoleon received Ney—who exhausted himself in ridiculous excuses—with open arms. The night before, Ney had prepared an obscure letter, warning Napoleon that he should focus on the well-being of the French and to mend the harm his boundless ambition had inflicted upon them. Never one to listen to criticism, Napoleon dismissed the document, turning to his bystanders, “This fine fellow Ney is going mad.”

Though Napoleon showed cordiality, he did not trust Ney, who seemed more unpredictable and labile than ever while also harbouring a deep, brooding self-doubt. After sensationally reclaiming the French throne, Bonaparte did not employ Ney until the dramatic finale of the Napoleonic saga.

“Long live Ney!”

Only when the reinstated Napoleon marched his troops toward modern-day Belgium with the plan to quickly and decisively crush Blücher’s Prussians and Wellington’s mixed army of British, Dutch, Belgians, and Germans, he invited Ney to join him and take command of his left flank, a considerable force of up to 50,000 men.

After more than two decades of enduring the horrors of war, warfare was as natural to Ney as water to a fish. Knowing the unshakable devotion of France’s soldiery toward him, he did not hesitate to accept the call.

This belated invitation was not least due to scarcity of available Marshals. Some had fallen in battle, others now ruled foreign lands, while a few had retired—whether by age or caution. Some were ill, others outright foes, and the rest were either tasked with staff duties or maintaining the fragile peace in Paris.

The summer campaign started promisingly, with Napoleon driving the Prussians from the field at Ligny while Ney simultaneously engaged his old foe from the Peninsular War, Duke Wellington, at Quatre-Bras.

However, since communication and organisation of the French army was as amateurish as in ages, the reserve corps failed to arrive in time for either battle, squandering a critical opportunity. Thus, the Prussians got away with a scare, and Wellington managed to withdraw to Waterloo and position his troops along the gentle incline of Mont St. Jean, positioned across the road to Brussels.

Only one of Napoleon’s Marshals was destined to take centre stage in the climactic battle that would unfold two days later. Curiously, Napoleon, plagued by bad health but aware of Ney’s limitations and his mistakes at Quatre-Bras, entrusted the red-haired Marshal to run most of the all-important battle. For his fanatical performance at Waterloo, Ney would go on to cement his place in history. It was a fitting finale to the tale of a man who had been in nearly ceaseless combat for the twenty-three years prior.

The first French infantry attacks were beaten back by about 14:30. Ney, as always, was in the thick of battle, fighting with frenzied intensity and leading on the assault battalions. Yet his demeanour had shifted. During the gruelling retreat from Russia, he had been restrained, urging his men on with grim humour. But even steel bends before it breaks.

Now, in his final battle, he seemed isolated, his constant anger and rage betraying a deeply tormented soul. Two days earlier, at Quatre Bras, he had been heard murmuring, “If only an English bullet would end me!” At Waterloo, it seemed to some as though he was deliberately seeking death. Delderfield has asked the question if this was “the result of a tortured conscience or the death wish a man might develop after a life dedicated to war?”[4]

Foiled in his infantry attacks and mistaking the British carrying away their wounded as a sign of retreat, Ney, now acting without orders, put himself at the head of the heavy cavalry. It was time for the former hussar’s trademark action: the do-or-die-charge. Ney had assembled close to 10,000 horsemen and spectacularly threw them at the British centre. It was a terrifying sight. “The very earth seemed to vibrate beneath the thundering tramp,” as one British eyewitness recalled.

But Wellington’s artillerymen held their fire with iron discipline, waiting until the last possible moment when the enemy cavalry was almost upon them. Then, they unleashed a devastating hail of canister shot, cutting down the leading ranks of the attack. Despite all its ferocity, the charge faltered.

The cavalry could not break the steadfast British square formations that stood unyielding. Unfazed, Ney rallied his men and launched a dozen more furious cavalry charges against the British, each attack more desperate and hopeless than the last.

While generally mindful of the lives of his men, the horrors to which Ney now exposed them claimed a heavy blood toll. Those under his command could not help but observe that, instead of lifting their spirits with his usual sharp humour, Ney dealt out verbal blows—berating, cursing, and driving them on with threats.

Ney barked at a division general as if he were a common ranker: “Damn you, general! Where is your honour? Has your courage deserted you, monsieur? Do you no longer serve the Emperor? Form your troopers up, charge that square, and be quick about it!”

As evening fell, the arrival of the Prussians on the French right increased the pressure dramatically. Napoleon, sensing the looming spectre of ultimate defeat, realized the time had come to risk everything on one final attack. He called upon his vaunted Imperial Guard to finally break the British lines.

Once more, it was Ney who led the charge, now on foot and miraculously still unharmed as no less than five horses had been shot under him. “The bravest of the brave” spurred forward at the head of the Guard, advancing straight into the jaws of the British defence in two massive columns.“Come and see how a Marshal of France can die!” he roared, and half to himself added, “we shall be hanged if we live through this.”

But the elite Guard, caught in a deadly crossfire of artillery and shredded by point-blank musket volleys, began to waver. As even Napoleon’s famous bearskins faltered, a wave of panic swept through the army.

The indomitable Ney refused to retreat, shouting pointlessly at the fleeing men to attack again. “Long live Ney!” some of them cried as they streamed past him, their voices filled with admiration even during despair.

Napoleon’s last army was in full retreat, and as the summer dusk gathered over the blood-soaked fields near Brussels, the sun was setting on both the empire and Ney.

“I shall know how to die like a Frenchman!”

When the Bourbons quickly returned to their palaces and Napoleon was exiled to St. Helena, his anxious supporters scrambled to justify their actions during the so-called Hundred Days. Though the capitulation treaty promised amnesty for Bonapartists, the aristocracy sought to erase their disgraceful flight from Paris by spilling the blood of the most prominent defector—Marshal Ney.

Only his co-Marshals Davout and St. Cyr could persuade Ney to flee Paris, as he remained contemplative and oblivious to the brewing danger. After a brief refuge in a remote château, he was recognized, arrested, and brought back to Paris in August 1815. Ney made no effort to resist and refused several offers to help him escape. He wanted to publicly clear the perceived stain on his honour.

King Louis, one of the few Bourbons wary of revenge, upon hearing the news was dismayed, dreading a public trial of the popular Ney. “Why did he let himself be caught? We gave him every chance to get away!” he lamented.

Eager for retribution, the aristocrats lost no time in trialling their famous prisoner. Marshal Moncey was ordered to head a high-ranking court-martial, which he courageously refused, writing to the King: “At the Berezina it was Ney who saved the remnants of the army, (…) a man to whom so many Frenchmen owe their lives, so many families their sons, husbands, fathers!”

After much hesitation, the seven-member court-martial—including Marshals Jourdan, Augereau, Mortier, and Ney’s old rival Masséna—declared itself “non-competent,” conveniently yet faint-heartedly shifting responsibility back to the Bourbons.

Ney’s wife, Aglaé, made many desperate appeals to influential figures, including the Duke of Wellington, a signatory of the capitulation’s amnesty. However, Ney’s former opponent in Iberia and at Waterloo lacked the backbone to intervene in the juridical farce that was a flagrant violation of the armistice.

The main charge against Ney was the baseless claim that he had not only defected to Napoleon but had done so as part of a larger plan devised while Bonaparte was still in exile on Elba. An arch-royalist general who was with Ney before joining Napoleon falsely accused Ney of wearing an Imperial Eagle decoration just minutes after switching sides.

Conducting himself with great dignity, Ney defended himself, asserting that he had turned his back on the Bourbons only after realizing his troops would refuse to fight against Napoleon and that he was protected by the amnesty. When his lawyer brought forward the argument that Saarlouis, the Marshal’s birthplace, was no longer French but Prussian, Ney interrupted: “I am French and will remain French. I shall know how to die like a Frenchman!” And so, it came to be.

The trial was moved to the Chamber of Peers. The Bourbon’s façade parliament was composed mostly of loyalist aristocrats but also members of the Napoleonic nobility. The hardcore royalists wanted to set an example, while many of the former Bonapartists, eager to prove their loyalty, saw the show trial as an opportunity to redeem themselves. The outcome was a foregone conclusion.

By a vote of 170 to 47, Ney was found guilty of treason. 139 peers voted for death, 17 for deportation and only five abstained, recommending clemency from the King. Among those who voted for the death penalty were more than twenty military officers, many of whom had served with Ney. The most prominent of them were Marshals Marmont, Victor, Kellerman, Perignon, and Sérurier.

On the morning of 7 December 1815, beneath a grey sky and a thin, miserable drizzle, Ney was brought to the Luxembourg Gardens in Paris and lined up against a stone wall. Twelve veterans were lined up in front of him, their muskets loaded. Ney refused to kneel and wear a blindfold.

Calm and noble as ever, he removed his hat, took a few steps forward, and, in a firm, unwavering voice, gave his final command:

Soldiers, when I give the command to fire, fire straight at my heart. Wait for the order. It will be my last to you. I protest against my condemnation. I have fought a hundred battles for France, and not one against her…Soldiers, fire!

Struck down by eleven shots, Ney immediately collapsed, dying with the same unshakable courage that had defined his life. For a quarter of an hour, “Le Brave des Braves” lay face-first in the Paris mud.

Epilogue

In his second exile, when Napoleon attempted to review his incredible life and to deny blame for Waterloo, his verdict on Ney was rather uncharitable: “He was good for a command of 10,000 men, but beyond that, he was out of his depth.”

Napoleon certainly has a point, as Ney was poor as an independent commander, decent as a corps commander and excellent in leading divisions. He was at his best when executing Napoleon’s direct orders, a sharp blade that only needed the right hand to wield it. With his undeniable bravery and keen tactical instinct, Ney was both a formidable weapon and a steadfast paladin. His greatest gift, however, lay in his ability to inspire and rally half-hearted men—a skill in which he had no equal.

As an exceptional judge of character, Napoleon understood that Ney could be somewhat of a rash opportunist who made critical decisions on the fly, often without considering the consequences until it was too late. About his tragic death, Bonaparte harshly remarked, “Ney only got what he deserved. I regret him as a man very precious on the battlefield, but he was too immoral, too stupid to be able to succeed.”

Ney was a simple man whose incredible and impetuous heroism on the battlefield helped him to achieve wealth and the highest honours in an age of profound social change. His indecisiveness and lack of instinct outside the battlefield eventually were his undoing. Even more so, however, were his many traumatic experiences of two decades of war, which probably caused severe combat fatigue. At the end of his life, Ney remembered that after shifting allegiances to Napoleon in 1815, “I wished only for death, and many times I had the idea of blowing my brains out!”

It is not without irony that Ney, who for two decades had frantically thrown himself into enemy musketry—and at the later stages of his career had sought a battlefield death—ultimately met his end not in combat, but by French bullets, in an execution he could have easily escaped.

His death was pointless and a cruel show of force, but at age 45, Ney “was a man who had seen and done too many terrible things and wanted to be relieved of the joyless burden of life.”[5] After all, it was Ney’s opponent, the Duke of Wellington, who had once remarked that “nothing except a battle lost can be half so melancholy as a battle won.”

In an epic era, Marshal Michel Ney was one of its most heroic figures, yet he was also a relentless man in a merciless age. The upheavals of the Revolution and Napoleon’s faible for meritocracy had catapulted him and many of his brothers-in-arms from humble backgrounds to unprecedented heights. It was an ascent that came at a heavy price, though.

For all his incredible courage, Ney could not escape the shadows of war—a grim, unpitying force that may forge plenty of heroes but never fails to sow far greater harvests of suffering and despair.

[1] Delderfield, Napoleon’s Marshals, 20.

[2] Delderfield, 12.

[3] Oman, A History of the Peninsular War Vol. 3, 263.

[4] Delderfield, Napoleon’s Marshals, 211.

[5] Danielski, „Marshal Ney and PTSD — Did the Mental Health Affliction Shatter Napoleon’s ‘Bravest’ Marshal?“

(If you enjoyed the text, please leave a like!)